Category: Orthopedics

Keywords: SEA, ESR, spinal infection (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/24/2021 by Brian Corwell, MD

Click here to contact Brian Corwell, MD

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) for spinal infection

Sensitive for spinal infection but not specific

Elevated ESR is observed in greater than 80% of patients with vertebral osteomyelitis and epidural abscess

ESR is the most sensitive and specific serum marker for spinal infection

Usually elevated in acute presentations of SEA and vertebral osteomyelitis

ESR was elevated in 94-100% of patients with SEA vs. only 33% of non-SEA patients

Mean ESR in patients with SEA was significantly elevated (51-77mm/hour)

Infection is unlikely in patients with an ESR less than 20 mm/h.

Incorporating ESR into an ED decision guideline may improve diagnostic delays and help distinguish patients in whom MRI may be performed on a non-emergent basis

1) Davis DP, et al. Prospective evaluation of a clinical decision guideline to diagnose spinal epidural abscess in patients who present to the emergency department with spine pain. J Neurosurg Spine 2011;14:765-767.

2) Reihsaus E, et al. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev 2000;23:175,204

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: COPD, emphysema, acute respiratory failure, hypoxia, oxygen saturation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/20/2021 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

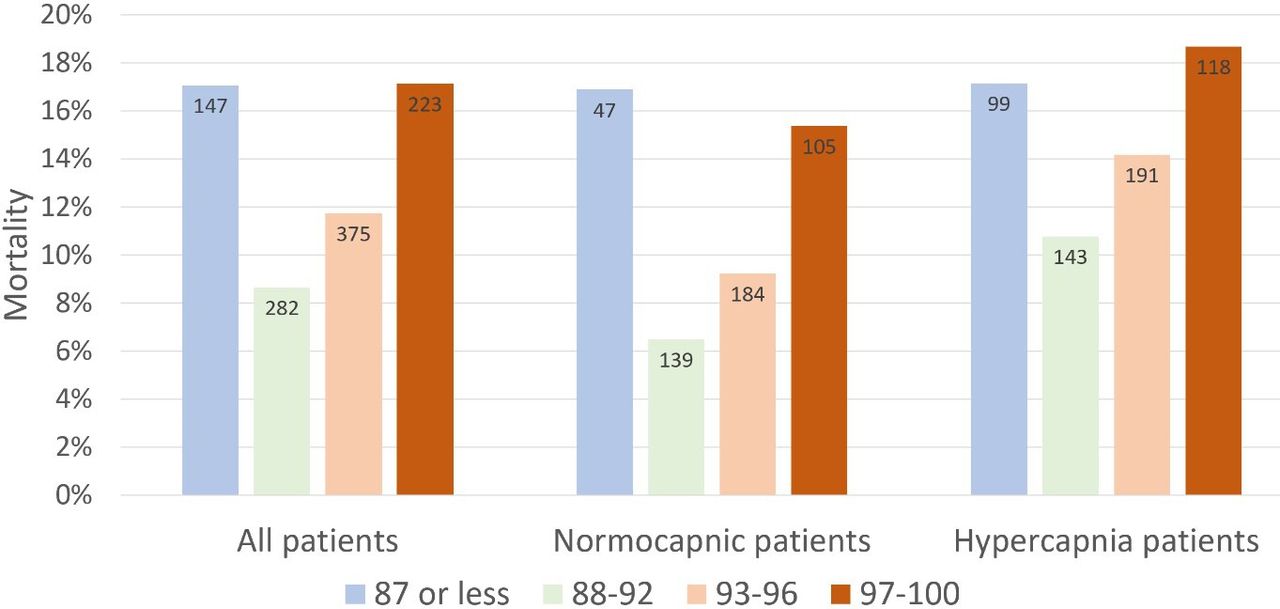

Supplemental oxygen therapy is frequently required for patients presenting with acute respiratory distress and COPD exacerbation. Over-oxygenation can derail compensatory physiologic responses to hypoxia,1 resulting in worsening VQ mismatch and, to a lesser degree, decreases in minute ventilation, that cause worsened respiratory failure.

The 2012 DECAF (Dyspnea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidaemia, and Atrial Fibrillation) score was found to predict risk of in-hospital mortality in patients admitted with acute COPD exacerbation.2,3 Data from the DECAF study’s derivation and external validation cohorts were examined specifically to look at outcome associated with varying levels of oxygen saturation.

Bottom Line

In patients presenting to the ED with acute COPD exacerbation requiring oxygen supplementation, a target oxygen saturation of 88-92% is associated with the lowest in-hospital mortality, and higher oxygen saturations should be avoided independent of patients' PCO2 levels.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: stroke, altered mental status, TPA (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/16/2021 by Jenny Guyther, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Baldovsky MD, Okada PJ. Pediatric stroke in the emergency department. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020 Oct 6;1(6):1578-1586. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12275. PMID: 33392566; PMCID: PMC7771757.

Category: Neurology

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, alteplase, tPA, thrombolysis, error (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/15/2021 by WanTsu Wendy Chang, MD

Click here to contact WanTsu Wendy Chang, MD

Bottom Line: Alteplase administration in acute ischemic stroke is associated with errors, most commonly with over-dosage of the medication.

Dancsecs KA, Nestor M, Bailey A, Hess E, Metts E, Cook AM. Identifying errors and safety considerations in patients undergoing thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;47:90-94.

Follow me on Twitter @EM_NCC

Category: Orthopedics

Keywords: Concussion, mTBI, exercise prescription (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/10/2021 by Brian Corwell, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Brian Corwell, MD

A total of 367 patients were enrolled. Median age was 32 years Male 43%/Female 57%.

Result: There was no difference in the proportion of patients with postconcussion symptoms at 30 days. There were no differences in median change of concussion testing scores, median number of return PCP visits, median number of missed school or work days, or unplanned return ED visits within 30 days. Participants in the control group reported fewer minutes of light exercise at 7 days (30 vs 35).

Conclusion

Prescribing light exercise for acute mTBI, demonstrated no differences in recovery or health care utilization outcomes.

Extrapolating from studies in the athletic population, there may be a patient benefit for light exercise prescription.

Make sure that the patient is only exercising to their symptomatic threshold as we recommend with concussed athletes. Previous studies have shown that athletes with the highest post injury activity levels had poorer visual memory and reaction time scores than those with moderate activity levels.

Varner et al. A randomized trial comparing prescribed light exercise to standard management for emergency department patients with acute mild traumatic brain injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2021.

Category: Toxicology

Keywords: household spices, abuse, toxicity (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/8/2021 by Hong Kim, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Hong Kim, MD

There are three commonly household spices that can be abuse/misused or cause toxicity after exposure.

Pure vanilla extract contains at least 35% ethanol by volume per US Food and Drug Administration standards

Nutmeg contains myristicin – serotonergic agonist that possess psychomimetic properties.

Clinical effects:

Cinnamon contains cinnamaldehyde and eugenol – local irritants.

Johnson-Arbor K et al. Stoned on spices: a mini-review of three commonly abuse housenold spices. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020

https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2020.1840579

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: COVID-19, Anticoagulation, Thromboembolism (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/7/2021 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Two items from the recent INSPIRATION trial UMEM pearl were very well pointed out by our own Dr. Michael Scott and require clarification. Thank you to all our readers for their close attention, and please know that we always appreciate you reaching out with questions/comments.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: COVID-19, Anticoagulation, Thromboembolism (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/7/2021 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

COVID-19 is generally regarded as a hypercoagulable state, and the role of pulmonary emboli and other VTE in COVID remains unclear. As a result, how to optimally provide prophylactic anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients who are not known to have VTE has been a point of debate.

The INSPIRATION trial looked at 600 patients admitted to academic ICUs in Iran, and compared what is often-referred to as "intermediate-dose" prophylaxis (in this case 1 mg/kg daily of enoxaparin) to standard dose prophylaxis (40 mg/day of enoxaparin). The study utilized a combined endpoint of venous thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, need for ECMO, or mortality. As a reminder, composite endpoints can skew results. However, the dose and type of anticoagulant chosen is similar to many academic centers around the world, and pharmacy guidelines often recommend providing this type of "intermediate-dose" prophylaxis in COVID-19 patients, sometimes based on clinical status, d-dimer or other coagulation-related patient-data. As with many things with COVID-19, this practice is based on limited data.

There was no significant difference between groups in the primary outcome (45.7% in intermediate ppx group vs 44.1% in standard group), and while safety outcomes were similar (major bleeding in 2.5% in the intermediate ppx group vs 1.4% in standard group), the intermediate regimen failed to demonstrate non-inferiority to the standard regimen for major bleeding.

Intermediate vs standard-dose ppx was similar in this study with a small, but statistically significant increase in major bleeding in the intermediate-dose group.

Bottom Line: Although this study had methodologic flaws and there are external validity concerns, the INSPIRATION trial supports the notion that standard dose (e.g. 40 mg/g/kg/day enoxaparin) and intermediate-dose (e.g. 1 mg/kg/day enoxaparin) VTE prophylaxis are equivalent in critically ill COVID-19 patients who do not already have a known VTE in terms of preventing negative VTE outcomes. Intermediate-dose may be associated with increased bleeding. As more critically ill patients require ED boarding, the dose of VTE prophylaxis may remain controversial, but the need to start it remains an important consideration.

INSPIRATION Investigators, Sadeghipour P, Talasaz AH, Rashidi F, Sharif-Kashani B, Beigmohammadi MT, Farrokhpour M, Sezavar SH, Payandemehr P, Dabbagh A, Moghadam KG, Jamalkhani S, Khalili H, Yadollahzadeh M, Riahi T, Rezaeifar P, Tahamtan O, Matin S, Abedini A, Lookzadeh S, Rahmani H, Zoghi E, Mohammadi K, Sadeghipour P, Abri H, Tabrizi S, Mousavian SM, Shahmirzaei S, Bakhshandeh H, Amin A, Rafiee F, Baghizadeh E, Mohebbi B, Parhizgar SE, Aliannejad R, Eslami V, Kashefizadeh A, Kakavand H, Hosseini SH, Shafaghi S, Ghazi SF, Najafi A, Jimenez D, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sethi SS, Parikh SA, Monreal M, Hadavand N, Hajighasemi A, Maleki M, Sadeghian S, Piazza G, Kirtane AJ, Van Tassell BW, Dobesh PP, Stone GW, Lip GYH, Krumholz HM, Goldhaber SZ, Bikdeli B. Effect of Intermediate-Dose vs Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation on Thrombotic Events, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment, or Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: The INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021 Mar 18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4152. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33734299.

Category: Pharmacology & Therapeutics

Keywords: Pyelonephritis, Outpatient, Fluoroquinolones, TMP-SMX, Beta-lactams (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/3/2021 by Wesley Oliver

Click here to contact Wesley Oliver

While fluoroquinolones have fallen out of favor for many indications due to the ever growing list of adverse effects, they still play an important role in the outpatient treatment of pyelonephritis. Fluoroquinolones and TMP-SMX are the preferred agents due to higher failure rates with beta-lactams.

Preferred Therapies:

Ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO BID*

Levofloxacin 750 mg PO daily*

TMP-SMX 1 DS tab PO BID**

*Consider a single dose of long-acting parenteral agent, such as ceftriaxone, if community prevalence of fluoroquinolone resistance >10%.

**Consider a single dose of long-acting parenteral agent, such as ceftriaxone, if using TMP-SMX.

Alternative Therapies#:

Cefpodoxime 200 mg PO BID

Cefdinir 300 mg PO BID

#Beta-lactams are not preferred agents due to higher failure rates when compared to fluoroquinolones. Consider a single dose of long-acting parenteral agent, such as ceftriaxone, if using beta-lactams.

Duration of Therapy: 10-14 days

Take Home Point:

Utilize ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, or TMP-SMX over beta-lactams when discharging patients with oral antibiotics for pyelonephritis.

Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e103.

Urinary Tract Infections. UMMS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Sanford Guide, 2021. Accessed April 2, 2021. https://webedition.sanfordguide.com/en/umms/syndromes/urinary-tract-infections.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/30/2021 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Improving Compliance with Lung-Protective Ventilation

Tallman CMI, et al. Impact of provding a tape measure on the provision of lung-protective ventilation. West J Emerg Med. 2021; 22:389-93.

Category: Toxicology

Keywords: diphenhydramine overdose, seizure, ventricular dysrhythmia, severe toxicity (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/25/2021 by Hong Kim, MD

Click here to contact Hong Kim, MD

Diphenhydramine is commonly involved in overdose or misused. Although it is primarily used for its anti-histamine property, it also has significant antimuscarinic effect.

A recent retrospective study investigated the clinical characteristics associated with severe outcomes in diphenhydramine overdose using the multi-center Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) Registry.

Severe outcomes were defined as any of the following:

Results

863 cases of isolated diphenhydramine ingestion were identified between Jan 1, 2010 to Dec 31, 2016

Most common symptoms:

Factors associated with severe outcome

Conclusion

Hughes AR et al. Clinical and patient characteristics associated with severe outcome in diphenhydramine toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2021.

Category: Pediatrics

Keywords: Chest pain, ischemia, pediatrics, myocarditis (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/19/2021 by Jenny Guyther, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Jenny Guyther, MD

Even though acute myocardial ischemia (AMI) does not present as commonly in the pediatric patient as in the adult and the literature is limited, it is reasonable to obtain a troponin when acute cardiac ischemia is suspected based on the history and physical exam.

Recreational drugs including cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis, Spice, and K2 (cannabis derivatives) have been shown to result in myocardial injury including AMI. Coronary vasospasm secondary to drug use is well documented in the pediatric population. While cocaine use is a known risk factor for coronary vasospasm, the same condition has been reported in pediatric patients after marijuana use.

In a study of pediatric patients with blunt chest trauma, 3 of 4 patients with electrocardiographic or echocardiographic evidence of cardiac injury had elevations in troponin I above 2.0 ng/mL. Cardiac troponins are an accurate tool for screening for cardiac contusion after blunt chest trauma in pediatric patients even with limited data.

Cardiac troponins are also useful in the evaluation for myocarditis. In one study, myocarditis was the most common diagnosis (27%) in pediatric ED patients presenting with chest pain and an increased troponin. Eisenberg et al showed a 100% sensitivity and an 85% specificity for myocarditis using a troponin of 0.01 ng/mL or greater as a cut off. A normal troponin using this cutoff can be used to exclude myocarditis. Abnormal troponin in the first 72 hours of hospitalization in pediatric patients with viral myocarditis is associated with subsequent need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and IVIg.

Bottom line: Troponin can be used in pediatric patients with clinical concern for cardiac ischemia, cardiac contusion and myocarditis

Brown JL, Hirsh DA, Mahle WT. Use of troponin as a screen for chest pain in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012;33(2):337-342. doi:10.1007/s00246-011-0149-8

Drossner DM, Hirsh DA, Sturm JJ, et al. Cardiac disease in pediatric patients presenting to a pediatric ED with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(6):632-638. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.011

Thankavel PP, Mir A, Ramaciotti C. Elevated troponin levels in previously healthy children: value of diagnostic modalities and the importance of a drug screen. Cardiol Young. 2014;24(2):283-289. doi:10.1017/S1047951113000231

Yolda? T, Örün UA. What is the Significance of Elevated Troponin I in Children and Adolescents? A Diagnostic Approach. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;40(8):1638-1644. doi:10.1007/s00246-019-02198-w

Adams JE, Dávila-Román VG, Bessey PQ, Blake DP, Ladenson JH, Jaffe AS. Improved detection of cardiac contusion with cardiac troponin I. Am Heart J. 1996;131(2):308-312. doi:10.1016/s0002-8703(96)

Hirsch R, Landt Y, Porter S, et al. Cardiac troponin I in pediatrics: normal values and potential use in the assessment of cardiac injury. J Pediatr. 1997;130(6):872-877. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(97)

Eisenberg MA, Green-Hopkins I, Alexander ME, Chiang VW. Cardiac troponin T as a screening test for myocarditis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(11):1173-1178. doi:10.1097/PEC.

Category: Toxicology

Keywords: occupational poisoning (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/18/2021 by Hong Kim, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Hong Kim, MD

There are different occupational hazards depending on the nature of one’s trade/skill/employment. Although healthcare providers may not always inquire about patient’s occupation, knowledge of a patient’s occupation may provide insightful information when caring for patients with acute poisoning.

From a recent retrospective study of National Poison Data System, the top 10 occupational toxicants were:

Top 10 occupational toxicants associated with fatalities were:

Downs JW et al. Descriptive epidemiology of clincally signifcant occupational poisonings, United States, 2008-2018. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021. PMID: 33703981

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/16/2021 by Lindsay Ritter, MD

Click here to contact Lindsay Ritter, MD

The PARAMEDIC2 trial in NEJM 2018 studied the outcomes of the use of epinephrine in outside hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) on survival and neurological outcome.

Methods: Conducted in Britain, randomized 8007 patients to receive either epinepherine 1mg (n=4012) or placebo (n=3995) as part of standard CPR for out-of-hosptial arrest. Their primary outcome was survival at 30 days and their secondary outcomes included length of stay as well as neurological outcomes at 30 days and 3 months.

Results: The epinepherine group had improved survival to hospital admission (23% vs. 8%), at 30 days (3.2% vs. 2.4%) or at 3 months (3% vs. 2.2%). Favourable neurological outcomes, however, had no statistical difference at both hospital discharge and at 3 months.

Bottom line: Epinephrine improves ROSC, though with poor neurological outcomes.

Important facts:

Recently, a follow up of the PARAMEDIC2 trial was completed in Resuscitation.

They reported long-term survival, quality of life, functional and cognitive outcomes at 3, 6 and 12-months.

Results: At 6 months, 78 (2.0%) of the patients in the adrenaline group and 58 (1.5%) of patients in the placebo group had a favourable neurological outcome (adjusted odds ratio 1.35 [95% confidence interval: 0.93, 1.97]). 117 (2.9%) patients were alive at 6-months in the adrenaline group compared with 86 (2.2%) in the placebo group (1.43 [1.05, 1.96], reducing to 107 (2.7%) and 80 (2.0%) respectively at 12-months (1.38 [1.00, 1.92]). Measures of 3 and 6-month cognitive, functional and quality of life outcomes were reduced, but there was no strong evidence of differences between groups.

Bottom line: Epinephrine improves survival at 12 months, but poor neurological outcomes remain.

Haywood KL, Ji C, Quinn T, Nolan JP, Deakin CD, Scomparin C, Lall R, Gates S, Long J, Regan S, Fothergill RT, Pocock H, Rees N, O'Shea L, Perkins GD. Long term outcomes of participants in the PARAMEDIC2 randomised trial of adrenaline in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2021 Mar;160:84-93. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.01.019. Epub 2021 Jan 30. PMID: 33524488.

Perkins GD, Ji C, Deakin CD, Quinn T, Nolan JP, Scomparin C, Regan S, Long J, Slowther A, Pocock H, Black JJM, Moore F, Fothergill RT, Rees N, O'Shea L, Docherty M, Gunson I, Han K, Charlton K, Finn J, Petrou S, Stallard N, Gates S, Lall R; PARAMEDIC2 Collaborators. A Randomized Trial of Epinephrine in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 23;379(8):711-721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806842. Epub 2018 Jul 18. PMID: 30021076.

Category: Orthopedics

Keywords: patellofemoral, knee, pain (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/13/2021 by Michael Bond, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Michael Bond, MD

Bottom Line: In a recent meta-analysis the risk factors for patellofemoral syndrome are weak hip abduction strength, quadricep weakness in military recruits, and increased hip strength in adolescence.

PatelloFemoral Syndrome: Patellofemoral pain is not clearly understood and is believed to be multi-factorial. Numerous factors have been proposed including muscle weakness, damage to cartilage, patella maltracking, as well as others. Patient often complain of anterior knee that is aggravated by walking up and down stairs or squatting. Patellofemoral pain is extremely common. In the general population the annual prevalence for patellofemoral pain is approximately 22.7%, and in adolescents it is 28.9%.

Though commonly taught, the following have no evidence to support that they are a risk factor for patellofemoral syndrome: Age, Height, Weight, BMI, Body Fat or Q Angle of patella

Category: Neurology

Keywords: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, IIH, pseudotumor cerebri, obesity, healthcare utilization (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/10/2021 by WanTsu Wendy Chang, MD

Click here to contact WanTsu Wendy Chang, MD

Bottom Line: The incidence and prevalence of IIH is increasing, likely related to rising rate of obesity. This has also been associated with more healthcare utilization compared to the general population.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: sepsis recognition, antibiotics administration, mortality, (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/10/2021 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Background:

The association between time intervals of ED antibiotic administration and outcome has been controversial. While single studies showed there was increased mortality associated with delayed antibiotic administration (1-3). A meta-analysis of 13 studies and 33000 patients showed that there was no mortality difference between septic patients receiving immediate Abx (< 1 hour) vs. those receiving early abx (1-3 hours) (4).

Since delay in recognition of sepsis (defined as ED triage to Abx order) and delay in antibiotics delivery (Abx order to administration) contribute to total delay of Abx administration, a new retrospective study (3) attempted to investigate the contributions of either factor to hospital mortality.

Results:

The study used generalized linear mixed models and involved 24000 patients.

For All patients and outcome of hospital mortality:

Recognition delay (ED triage to Abx order): OR 2.7 (95% CI 1.5-4.7)*

Administration delay at 2-2.5 hours (Abx order to administration): OR 1.5 (1.1-2.0)

These results was associated with non-statistical significance in patients with septic shocks.

Conclusion:

Delayed recognition of sepsis was associated with higher hospital mortality. Longer delay of abx administration was also associated with increased risk of hospital mortality.

1.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al: Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:1589–1596

2. Ferrer R, Martin-Loeches I, Phillips G, et al: Empiric antibiotic treatment reduces mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock from the first hour: Results from a guideline-based performance improvement program. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: 1749–1755

3. Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al: Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:2235–2244.

4. Rothrock SG et al. Outcome of immediate versus early antibiotics in severe sepsis and septic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2020 Jun 24; [e-pub]. (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.042)

Category: Pharmacology & Therapeutics

Posted: 3/7/2021 by Ashley Martinelli

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Ashley Martinelli

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic medication that has been trialed in previous small studies to treat epistaxis. The data to this point has not reliably shown a reduction in bleeding at 30 minutes, but has demonstrated an increased rate of discharge at 2 hours and a reduction in re-bleeding events.

The NoPAC study was the largest study to date on TXA for epistaxis. It was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of TXA in adult patients with persistent atraumatic epistaxis to determine if TXA use decreased the rate of anterior nasal packing. Patients were excluded if they had trauma, out of hospital nasal packing, allergy to TXA, nasopharyngeal malignancy, hemophilia, pregnancy, or if they were referred to ENT.

Eligible patients completed 10 minutes of first aid measures followed by 10 minutes of topical vasoconstrictor application prior to randomization to either placebo of 200mg TXA soaked dental rolls inserted in the nare.

496 patients were enrolled. The average patient was 70 years old with stable vitals 150/80mmHg, HR 80 bpm with >60% on oral anticoagulants.

TXA did not reduce the need for anterior nasal packing: 100 (41.3% placebo) vs 111 (43.7% TXA) OR 1.11 (0.77-1.59). There were no differences in the rates of adverse events.

Bottom Line: TXA does not improve rates of anterior nasal packing for patients with persistent epistaxis.

Reuben A, Appelboam A, Stevens KN, et al. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce the need for nasal packing in epistaxis (NoPAC): Randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med 2021;1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.12.013

Category: Toxicology

Keywords: massive acetaminophen overdose, standard NAC, hepatotoxicity (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/4/2021 by Hong Kim, MD

Click here to contact Hong Kim, MD

Recently, there has been questions if standard n-acetylcysteine (NAC) dose is adequate for massive acetaminophen (APAP) overdose (ingestion of > 32 gm or APAP >300 mcg/mL).

A retrospective study from a single poison center (1/1/2010 to 12/31/2019) investigated the clinical outcome of massive APAP overdose (APAP > 300 mcg/mL at 4 hour post ingestion) treated with standard dosing of NAC.

Results

1425 cases of APAP overdose identified; 104 met the criteria of massive APAP overdose.

Among cases that received NAC within 8 hours post ingestion (n=44)

Among cases that received NAC > 8 hours post ingestion (n=60)

Odds of hepatotoxicity

Conclusion

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/2/2021 by Caleb Chan, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

Clinical Question:

Methods:

Results:

Take-home points:

Hughes CG, Mailloux PT, Devlin JW, et al. Dexmedetomidine or propofol for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis. N Engl J Med. Published online February 2, 2021:NEJMoa2024922.