Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/2/2024 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 2/9/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Noninvasive Ventilation for Preoxygenation

Gibbs KW, Semler MW, Driver BE, et al. Noninvasive ventilation for preoxygenation during emergency intubation. N Engl J Med. 2024; 390:2165-77.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: sepsis, septic shock, warning scores (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/25/2024 by Kami Windsor, MD

(Updated: 2/9/2026)

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Background: Sepsis remains a common entity associated with a relatively high rate of inpatient mortality, with timely recognition and treatment being key to improving patient outcomes. Various screening and warning scores have been created to attempt to identify sepsis and those patients at high risk of mortality earlier, but have limited performance because of suboptimal sensitivity and specificity.

A prospective observational study compared the performance of a variety of these scores (SIRS, qSOFA, SOFA, MEWS) as well as a machine learning model (MLM) against ED physician gestalt in diagnosing sepsis within the first 15 minutes of ED arrival.

Although not without its limitations, this study highlights the importance and relative accuracy of physician gestalt in recognizing sepsis, with implications for how to develop future screening tools and limit unnecessary exposure to unnecessary fluids and empiric broad spectrum antibiotics.

Bottom Line: In the era of machine learning models and AI, ED physicians are not obsolete. Even at 15 minutes, without lab results and diagnostics, our assessments lead to appropriate diagnoses and care. In this new normal of prolonged wait times and ED boarding, ED triage and evaluation models that optimize early physician assessment are of the utmost importance.

Knack SKS, Scott N, Driver BE, Pet al. Early Physician Gestalt Versus Usual Screening Tools for the Prediction of Sepsis in Critically Ill Emergency Patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2024 :S0196-0644(24)00099-4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2024.02.009.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: RSI, intubation, magnesium (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/18/2024 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Magnesium is known to relax smooth muscles. Interestingly, there is also some literature using it as part of Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) pre-treatment in general, in hopes that this or other mechanisms might allow it to improve intubating conditions. Zouche et al recently published an RCT looking at giving IV magnesium as part of RSI pretreatment in cases where neuromuscular blockade (NMB) is not going to be given (e.g. scenarios where it is contraindicated). IV Magnesium Sulfate, 50 mg/kg in 100 mL of saline given 15 minutes before induction, significantly improved intubating conditions in those getting sedation but not NMB (95% vs 39%).

In 2013, Park et al did an RCT giving magnesium to all RSIs, even with the use of rocuronium in those patients, arguing that magnesium is also known to potentiate the effects of non-depolarizing NMB agents. They also found better intubating conditions in the magnesium patients.

In both trials, magnesium was associated with lower heart rates and less hypertension in the peri-intubation and immediate post-intubation periods (of note: high dose magnesium is known to be associated with lower blood pressures, and can induce overt hypotension). Neither study was really powered for more important measures like first pass success, mortality, or important side effects like peri-intubation hypotension.

Bottom Line: These are two small trials, and while more abundant literature should probably be obtained before we change our practice, one could consider giving magnesium sulfate, 50 mg/kg in 100 mL saline, prior to intubation in an attempt to improve intubating conditions. In my opinion, this is probably worth considering in the rare circumstance that your patient has a true contraindication to neuromuscular blockade, but I probably wouldn't start doing this in standard RSI where you're going to be giving NMB until more literature confirms the safety of this approach. Also, I would avoid this in situations where the patient is already hypotensive or at high risk of peri-intubation hypotension. This may be worth considering in the very rare patient you're not necessarily going to give NMB to right away (maybe awake fiberoptic intubations?) who are also very low risk for hypotension.

Imen Zouche, Wassim Guermazi, Faiza Grati, Mohamed Omrane, Salma Ketata, Hichem Cheikhrouhou, Intravenous magnesium sulfate improves orotracheal intubation conditions: A randomized clinical trial, Trends in Anaesthesia and Critical Care, Volume 57, 2024, 101371, ISSN 2210-8440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tacc.2024.101371 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221084402400042X)

Park SJ, Cho YJ, Oh JH, Hwang JW, Do SH, Na HS. Pretreatment of magnesium sulphate improves intubating conditions of rapid sequence tracheal intubation using alfentanil, propofol, and rocuronium - a randomized trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013 Sep;65(3):221-7. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.65.3.221. Epub 2013 Sep 25. PMID: 24101956; PMCID: PMC3790033.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ICU, delirium, antipsychotic (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/18/2024 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Title: Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.

We all do it. When our patients in the ICU develop delirium, we would give them an antipsychotic, commonly quetiapine (Brand name Seroquel), and all is good. However, results from this most recent meta-analysis may suggest otherwise.

Settings: This is a meta-analysis from 5 Randomized Control Trials. Intervention was antipsychotic vs. placebo or just standard of care.

Participants: The 5 trials included A total of 1750 participants. All trials used Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU or Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist to measure delirium.

Outcome measurement: Delirium – and Coma-Free days

Study Results:

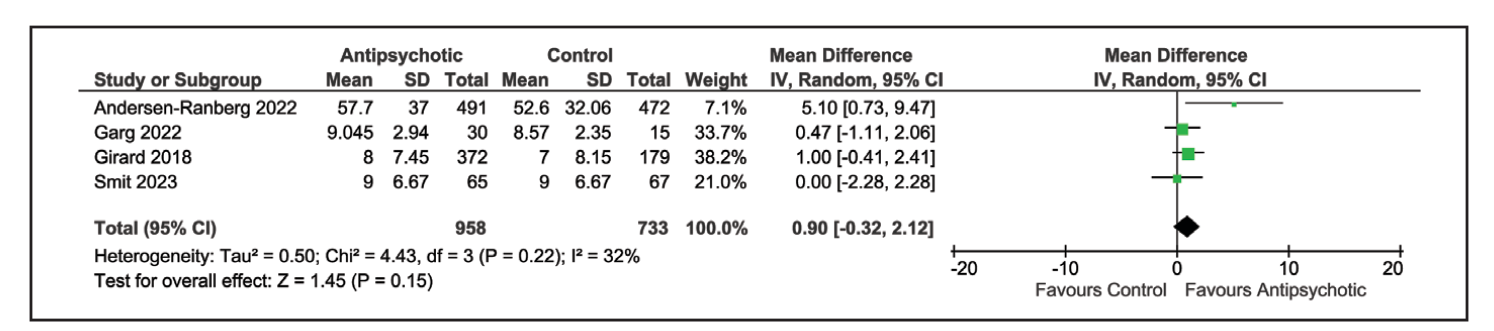

The use of any antipsychotic (typical or atypical) did not result in a statistically significant difference in delirium- and coma-free days among patients with ICU delirium (Mean Difference of 0.9 day; 95% CI -0.32 to 2.12).

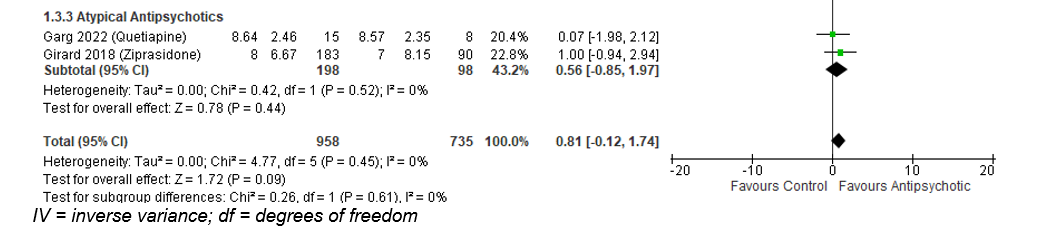

Similarly, atypical antipsychotic medication also did not result in difference of delirium- and coma-free days: Mean difference of 0.56 day; 95% CI -0.85 to 1.97).

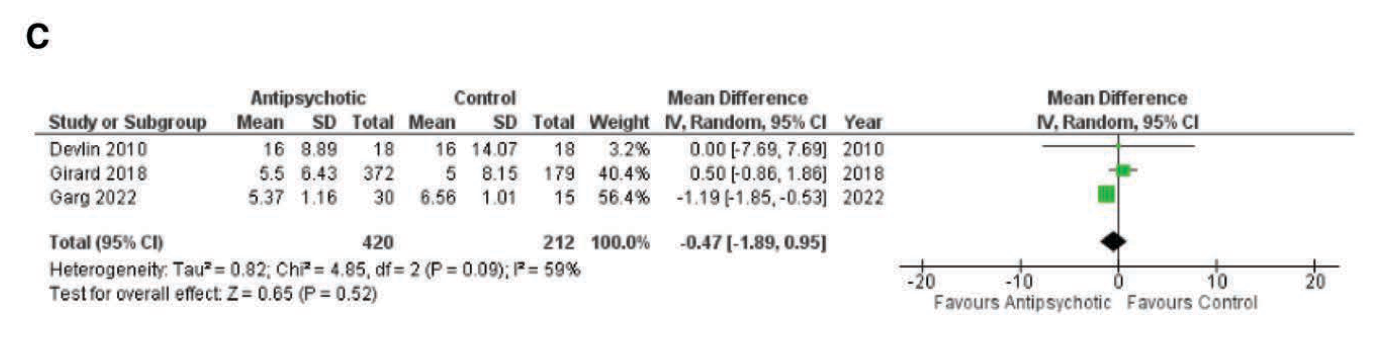

ICU length of stay was also not different in the group receiving antipsychotic: Mean difference -0.47 day, 95% CI -1.89 to 0.95).

Discussion:

The authors used both delirium -free and coma-free days as a composite outcome because they reasoned that delirium cannot be evaluated in unresponsive patients. This composite outcome might have affected the true incidence of delirium and the outcome of delirium-free days.

This meta-analysis would be different from previous ones that aimed to answer the same question. Previous studies compared either haloperidol vs a broader range of other medication (atypical antipsychotic, benzodiazepines) (Reference 2) or included all ICU patients with or without delirium who received haloperidol vs. placebo (Reference 3). Overall, those previous studies also reported that the use of haloperidol has not resulted in improvement of delirium-free days.

Conclusion:

There is evidence that the use of anti-psychotic medication does not result in difference of delirium- or coma-free days among critically ill patients with delirium.

1.Carayannopoulos KL, Alshamsi F, Chaudhuri D, Spatafora L, Piticaru J, Campbell K, Alhazzani W, Lewis K. Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Delirium in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit Care Med. 2024 Jul 1;52(7):1087-1096. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006251. Epub 2024 Mar 15. PMID: 38488422.

2. Andersen-Ranberg NC, Barbateskovic M, Perner A, Oxenbøll Collet M, Musaeus Poulsen L, van der Jagt M, Smit L, Wetterslev J, Mathiesen O, Maagaard M. Haloperidol for the treatment of delirium in critically ill patients: an updated systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Crit Care. 2023 Aug 26;27(1):329. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04621-4. PMID: 37633991; PMCID: PMC10463604.

3. Huang J, Zheng H, Zhu X, Zhang K, Ping X. The efficacy and safety of haloperidol for the treatment of delirium in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Jul 27;10:1200314. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1200314. PMID: 37575982; PMCID: PMC10414537.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 6/11/2024 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

Many patients present to the ED with hypercarbic respiratory failure (i.e. COPD exacerbation, obesity hypoventilation syndrome etc.). Typically, our first line of treatment is the use of BiPAP, where we set an inspiratory pressure (IPAP) and an expiratory pressure (EPAP). The difference between these two pressures (as well as patient effort) determines the tidal volumes (and consequently minute ventilation) a patient receives in our attempts to help the patient “blow off CO2.”

If you are having trouble with continued hypercarbia despite the use of BiPAP, another NIPPV mode that can be trialed is Average Volume-Assured Pressure Support (AVAPS). With BiPAP the patient receives the same fixed IPAP no matter what, even if their tidal volumes are lower than what is needed. With AVAPS, the ventilator will self-titrate the IPAP and increase (or decrease) the IPAP to reach the tidal volumes that you set, increasing the odds the patient will achieve the minute ventilation you are trying to achieve.

(AVAPS is essentially a non-invasive version of PRVC)

Initial settings (ask your RTs for help!):

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 6/4/2024 by William Teeter, MD

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

This really interesting study suggests that the classic site of CPR “in the middle of the chest” may actually not be the ideal place to perform CPR. Previous imaging studies demonstrate that the ventricles are primarily beneath the lower third of the sternum and that standard placement of CPR compressions may deform the aortic valve, blocking the LVOT, and theoretically limiting perfusion of the coronaries and brain.

This study compared a standard CPR group with those undergoing TEE-guided chest compressions to avoid aortic valve compression. Those in the non-AV compression group had significantly increased likelihood of ROSC, survival to ICU, and higher femoral arterial diastolic pressures. However, there was no difference in long-term outcomes or end-tidal CO2.

Summary: Avoiding AV compression during CPR significantly improved the chance at ROSC in adult OHCA, but this small observational study did not show any difference in long term outcomes when compared to standard practice. Lowering the point of chest compressions in CPR to the lower third of the sternum may be beneficial.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 5/21/2024 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Historically, guideline recommendations have been to use a transfusion threshold of hemoglobin < 7 g/dL for patients unless they are a) undergoing orthopedic surgery or b) have cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Applefeld et al conducted a meta-analysis in 2018 which suggested that restrictive (i.e. lower hemoglobin trigger, typically 7-8) transfusion targets lead to worse outcomes in CVD patients than liberal (i.e. higher hemoglobin trigger, typically 9-10) targets, and those authors have updated this analysis to include data from newer trials. Interestingly, the conclusion remains similar: that when you look at the larger studies on restrictive vs liberal transfusion targets, CVD plays an important role, as patients with CVD tend to do better with liberal targets, and patients without CVD tend to do better with restrictive targets. Of note, CVD is variably defined in these studies, and sometimes limited only to active Acute Coronary Syndromes, and other times refers to all patients with acute or chronic CVD. However, according to their analysis, the aggregated data suggests that we should continue having higher transfusion targets in patients with CVD, and perhaps even more in the 9-10 range, as opposed to the goals of 7 or 8 which are common.

Bottom Line: We will likely continue to see different transfusion targets recommended for patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), and may even see guideline and blood bank recommendations raise the target for these patients more into the 9-10 range, or expand this group to include chronic CVD. This would mean a substantial increase in recommended RBC transfusions, and as emergency physicians it is important for us to monitor these recommendations, especially since transfusions are not harmless and raising hemoglobin thresholds could lead to complications that are difficult to measure in the literature.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 4/30/2024 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 2/9/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Title: Safety and Efficacy of Reduced-Dose Versus Full-Dose Alteplase for Acute Pulmonary Embolism: A Multicenter Observational Comparative Effectiveness Study

Settings: Retrospective observational study from a combination of Abbott Northwestern Hospital and 15 others as part of the Mayo Health system.

Participants: Patients between 2012 – 2020 who were treated for PE. Patients were propensity-matched according to the probability of a patient receiving a reduced- dose of alteplase.

Outcome measurement:

Study Results:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

In this retrospective, Propensity-score matching study, the full-dose regimen but is associated with a lower risk of bleeding.

Melamed R, Tierney DM, Xia R, Brown CS, Mara KC, Lillyblad M, Sidebottom A, Wiley BM, Khapov I, Gajic O. Safety and Efficacy of Reduced-Dose Versus Full-Dose Alteplase for Acute Pulmonary Embolism: A Multicenter Observational Comparative Effectiveness Study. Crit Care Med. 2024 May 1;52(5):729-742. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006162. Epub 2024 Jan 3. PMID: 38165776.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 4/23/2024 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

Background:

-Muscle rigidity has been described as a side-effect of fentanyl, specifically activation of expiratory muscles

-Excessive expiratory muscle use acts as “anti-PEEP,” causing lung derecruitment and hypoxemia

-End-expiratory lung volume (EELV) has been used as a surrogate for lung recruitment

Study:

-Small, two center, observational study (46 patients with ARDS)

-50% of patients had a significant increase in EELV after administration of neuromuscular blockade (NMB)

-Statistically significant correlation between a higher dosage of fentanyl and a greater increase in EELV after NMB

Takeaways:

-NMB can improve lung recruitment for a subset of patients with ARDS, particularly in patients with significant expiratory muscle use (this can be seen on your physical exam of your intubated ED boarding patient)

-Although this was not the main point of this study, consider fentanyl-associated “anti-PEEP,” particularly in patients receiving fentanyl whose hypoxemia and/or ventilator mechanics are disproportionate to their imaging

-This can be assessed with NMB (but ensure the patient will have adequate minute ventilation first)

-Naloxone has also been shown to reverse fentanyl-associated rigidity, but obviously would induce patient discomfort/withdrawal

*Of note, because this was an observational trial, it is possible that the patients with increased work of breathing were simply given more fentanyl. Regardless, these findings are consistent with previously documented physiologic side effects of fentanyl.

Plens GM, Droghi MT, Alcala GC, et al. Expiratory muscle activity counteracts positive end-expiratory pressure and is associated with fentanyl dose in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;209(5):563-572.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 4/17/2024 by William Teeter, MD

(Updated: 4/24/2024)

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

Moderate to High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism

In stable patients, call your local PE Response Team (PERT) for advice. The UMMC PERT team is available for any patient in the region and can be contacted through Maryland Access Center.

UMMC PERT stratifies by BOVA (with lactate criteria), CTA imaging, and patient physiology/history. For the consult, we will use the patients most recent vitals, their ROOM AIR sat if available, presence of RV dysfunction on echo/CTA, recent lactate, troponin, BNP, bedside/formal echo, and HPI.

Broad management recommendations for moderate or high-risk patients

PERT Acceptance for Transfer to UMMC/CCRU

See below for more information.

****************************************************************************************************************************************

Definitions of RV dysfunction

Absolute Contraindications to Fibrinolytic Therapy in Pulmonary Embolism

UMMC Relative Exclusion Criteria for VA ECMO for PE

HI-PEITHO (NCT04790370) “is a prospective, multicenter RCT comparing Ultrasound-facilitated catheter-directed therapy (USCDT) and best medical therapy (BMT; systemic anticoagulation) with BMT alone in patients with acute intermediate–high-risk PE.”

Inclusion Criteria

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: cardiac arrest, OHCA, airway, mechanical ventilation, resuscitation, bag-valve mask, manual ventilation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/10/2024 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

In cardiac arrest, avoidance of excessive ventilation is key to achieving HQ-CPR and minimizing decreases in venous return to the heart. The controversy regarding BVM vs definitive airway and OHCA outcomes continues, but data indicates that mechanical ventilation during CPR carries no more variability in airway peak pressures and tidal volume delivery than BVM ventilation [1], with the AHA suggestion to keep in-hospital cardiac arrest patients with COVID-19 on the ventilator during the pandemic [2].

So, can we automate this part of CPR?

Two recent studies looked at mechanical ventilation (MV) compared to bagged ventilation (BV) in intubated patients with out-of-hospital-cardiac arrest (OHCA).

Shin et al.'s pilot RCT evaluated 60 intubated patients, randomizing half to MV and half to BV, finding no difference in the primary outcome of ROSC or sustained ROSC, or ABG values, despite significantly lower tidal volumes and minute ventilation in the MV group [3].

Malinverni et al. retrospectively compared MV and BV OHCA patients from the Belgian Cardiac Arrest Registry, finding that MV was associated with increased ROSC although not with improved neurologic outcomes. Of note, patients across the airway spectrum were included (mask, supraglottic, intubated), and the mechanical ventilation was a bilevel pressure mode called Cardiopulmonary Ventilation (CPV) specific to their ventilators, specifically for use during cardiac arrest [4].

Bottom Line: Larger randomized trials will be necessary to get a definitive answer as to how mechanical ventilation affects outcomes in OHCA, but in instances where the cause of arrest is not primarily pulmonary (severe asthma, pneumothorax) and the ED is short-staffed or prolonged resuscitations are likely (such as in accidental hypothermic arrests), it is probably reasonable to keep patients on the ventilator:

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: IV Fluid, balanced solutions (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/3/2024 by Mark Sutherland, MD

(Updated: 2/9/2026)

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Multiple studies have suggested differences in patient outcomes with balanced solutions (e.g. plasmalyte) vs unbalanced solutions (e.g. normal saline) when large volumes are administered. But what about when giving smaller volumes of fluid? Does it matter which one you choose?

A recent study by Raes et al in the Journal of Nephrology looked at urine and serum effects of administering 1L of normal saline, vs 1L of plasmalyte, to ICU patients needing a fluid bolus. Chloride levels, strong ion difference (SID), and base excess were all significantly different between the two groups. There was no difference in blood pressure or need for vasopressors. As best I can tell, other clinically significant differences such as kidney injury were unfortunately not reported.

Bottom Line: When giving small (e.g. 1L) volumes of IVF, there ARE real physiologic differences seen between balanced and unbalanced solutions. Whether these differences translate to patient-oriented or clinically significant outcomes remains unclear.

Raes, M., Kellum, J. A., Colman, R., Wallaert, S., Crivits, M., Viaene, F., Hemeryck, M., Benoît, D., Poelaert, J., & Hoste, E. (2024). Effect of a single small volume fluid bolus with balanced or un-balanced fluids on chloride and acid–base status: a prospective randomized pilot study (the FLURES-trial). JN. Journal Of Nephrology (Milano. 1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-024-01912-z

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/26/2024 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Bag-Valve-Mask Ventilation During OHCA

Idris AH, et al. Bag-valve-mask ventilation and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A multicenter study. Circulation. 2023;148:1847-56.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: ROSC, OHCA, cardiac arrest, shock, vasopressors, norepinephrine, noradrenaline, epinephrine, adrenalin (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/19/2024 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Post-arrest shock is a common entity after ROSC. There is support for the use of continuous norepinephrine infusion over epinephrine to treat shock after ROSC, due to concerns about increased myocardial oxygen demand and associations with higher rates of rearrest [1,2] and mortality [2,3] with the use of epinephrine compared to norepinephrine, and increased refractory shock with use of epinephrine infusion after acute MI [4].

An article in this month’s AJEM compared norepinephrine and epinephrine infusions to treat shock in the first 6 hours post-ROSC in OHCA [5]. With a study population of 221 patients, they found no difference in the primary outcome of incidence of tachyarrhythmias, but did find that in-hospital mortality and rearrest rates were higher in the epinephrine group.

Bottom Line: Absent definitive evidence, norepinephrine should probably be the first pressor you reach for to manage post-arrest shock, especially if there is strong suspicion for acute myocardial infarction.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/12/2024 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 2/9/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Background: There is no clear guidelines regarding whether norepinephrine or epinephrine would be the preferred agent to maintain hemodynamic stability after cardiac arrest. In recent years, there has been more opinions about the use of norepinephrine in this situation.

Settings: retrospective multi-site cohort study of adult patients who presented to emergency departments at Mayo Clinic hospitals in Minnesota, Florida, Arizona with out-of-hospital-cardiac arrest (OHCA). Study period was May 5th, 2018, to January 31st, 2022

Participants: 18 years of age and older

Outcome measurement: tachycardia, rate of re-arrest during hospitalization, in-hospital mortality.

Multivariate logistic regressions were performed.

Study Results:

Discussion:

It was retrospective study that uses electronic health records. Thus, other important factors from the pre-hospital settings might not be accurate.

On the other hand, the patient population came from multiple hospitals with varying practices so the patient population is more generalizable.

Conclusion:

Although the rate of tachyarrhythmia was not different between patients receiving norepinephrine vs. epinephrine after ROSC. This study would add more data to the current literature that norepinephrine might be more beneficial for patients with post-cardiac arrest shock.

Normand S, Matthews C, Brown CS, Mattson AE, Mara KC, Bellolio F, Wieruszewski ED. Risk of arrhythmia in post-resuscitative shock after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with epinephrine versus norepinephrine. Am J Emerg Med. 2024 Mar;77:72-76. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2023.12.003. Epub 2023 Dec 10. PMID: 38104386.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: poisoning, intoxication, altered mental status, GCS, endotracheal intubation (PubMed Search)

Posted: 2/20/2024 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Background: Acutely intoxicated / poisoned patients are commonly encountered in the ED, with the classic teaching that a GCS < 9 is an indication to intubate for airway protection. But we’ve probably all had a patient who was borderline, or who we thought was still protecting their airway pretty well despite a lower GCS. Are we risking our patient’s health and our careers by holding off on intubation? Maybe not.

The NICO trial, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, looked at patients presenting by EMS with GCS <9 due to suspected poisoning, without immediate indication for intubation (defined by signs of respiratory distress with hypoxia, clinical suspicion of any brain injury, seizure, or shock with systolic BP <90 mmHg). They found that withholding intubation with close monitoring, compared to the standard practice of intubating at the EMS or ED physician’s discretion, resulted in:

Comparing the patients who were intubated in each group, there was no significant difference between groups in:

Notes:

Bottom Line: Without clear indication for intubation such as respiratory distress or accompanying head bleed, etcetera, intubation for mental status alone shouldn't be dogma in acute intoxication. Close monitoring will identify need for intubation, without apparent worsened outcomes due to a watchful waiting approach.

Freund Y, Viglino D, Cachanado M, et al. Effect of Noninvasive Airway Management of Comatose Patients With Acute Poisoning: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023; 330(23):2267-2274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.24391.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 2/6/2024 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

PEEP in the Ventilated COPD Patient?

Jubran A. Setting positive end-expiratory pressure in the severely obstructive patient. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2024; 30:89-96.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: sepsis, antibiotics, AKI, ACORN, zosyn, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/31/2024 by Kami Windsor, MD

(Updated: 2/9/2026)

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Background: For better or worse, the combination of “vanc-and-zosyn” has long been a go-to empiric regimen for the treatment of septic shock. Piperacillin-tazobactam is known to cause decreased creatinine secretion into the urine leading to an increased serum creatinine without any actual physiologic harm to the kidney, but the results of previous studies have led researchers to posit an increase in actual AKI with the vanc and zosyn combo. This concern has led to some physicians choosing cefepime for anti-pseudomonal gram-negative coverage instead, despite its known potential for neurotoxicity and cefepime-associated encephalopathy.

The ACORN trial: The recently published ACORN trial compared cefepime to piperacillin-tazobactam in adult patients presenting to the ED or medical ICU with sepsis or suspected serious infection. The primary outcome was a composite of highest stage of AKI or death at 14 days.

Results:

Bottom Line: Good antibiotic stewardship would probably decrease the frequency of vanc-and-zosyn administration, but concern for renal dysfunction alone shouldn’t guide the choice between cefepime or piperacillin-tazobactam, even in those with CKD, and even in those patients also receiving vancomycin.

Qian ET, Casey JD, Wright A, et al. Cefepime vs Piperacillin-Tazobactam in Adults Hospitalized With Acute Infection: The ACORN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023 Oct 24;330(16):1557-1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.20583.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: OHCA, elevated head and thorax, chest compression (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/23/2024 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Hot of the press from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (But most of us would know it already)

Settings: This is a prospective observational population-based study design with non-contemporaneous, nonrandomized clinical trial direct (unadjusted) head- to-head evaluations

Propensity score–matched comparisons of non-shockable cardiac arrest (NS-OHCA) patient survivor using conventional CPR (C-CPR) vs. C-CPR plus Automated Head/thorax up positioning-CPR (AHUP-CPR).

Participants: patients with non-traumatic, non-shockable out of hospital cardiac arrest (NS-OHCA).

Outcome measurement: primary outcome = survival, secondary outcome = survival with good neurologic outcome (Cerebral Performance Category score of 1–2 or modified Rankin Score less than or equal to 3).

Study Results:

• There was a total of 380 AHUP-CPR vs. 1852 C-CPR patients. After 1:1 matching, there were 353 AHUP-CPR patients and 353 C-CPR patients.

• In unadjusted analysis

o AHUP-CPR was associated with higher odds of survival (Odds ratio 2.46, 95% CI 1.55-3.92) and higher odds of survival with good neurologic function (Odds ratio 3.09 (95% CI 1.64-5.81)

• In matched groups

o AHUP-CPR was associated with higher odds of survival (Odds ratio 2.84, 95% CI 1.35-5.96) and higher odds of survival with good neurologic function [Odds ratio 3.87 (95% CI 11.27-11.78]

Discussion:

• There was no difference in rates of ROSC between groups. The authors argued that there was “neuroprotective effects” for the AHUP-CPR group.

• Although randomized controlled trials are usually required before clinical interventions are adopted, the aurthors argued that it would be difficult to randomize OHCA patients, and that the risk vs benefits may facilitate early adoption of this strategy.

• AHUP-CPR should be used first by well-trained clinicians to ensure its benefits.

Conclusion:

OHCA patients with NS presentations will have a much higher likelihood of surviving with good neurologic function when chest compressions are augmented by expedient application of the noninvasive tools to elevated head and thorax used in this study.

Bachista KM, Moore JC, Labarère J, Crowe RP, Emanuelson LD, Lick CJ, Debaty GP, Holley JE, Quinn RP, Scheppke KA, Pepe PE. Survival for Nonshockable Cardiac Arrests Treated With Noninvasive Circulatory Adjuncts and Head/Thorax Elevation. Crit Care Med. 2024 Feb 1;52(2):170-181. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006055. Epub 2024 Jan 19. PMID: 38240504.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: IVC, POCUS (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/17/2024 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

IVC POCUS is often misapplied in attempts to assess volume status and/or volume “responsiveness.” Here are some important concepts to understand when using IVC POCUS to guide management:

Rola P, Haycock K, Spiegel R. What every intensivist should know about the IVC. Journal of Critical Care. Published online November 2023:154455.