Category: Critical Care

Posted: 7/19/2022 by Caleb Chan, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

Tachyarrhythmias in the setting of high-dose vasopressors due to septic shock are not uncommon. Aside from amiodarone, some providers may not know of alternative therapeutic options in the setting of septic shock. In addition, some may view the use of a beta-blocker as counter-intuitive or counter-productive in the setting of norepinephrine usage.

However, there have been multiple smaller studies evaluating using esmolol (and other short-acting beta-blockers) in the setting of tachycardia, septic shock and pressors. Outcomes regarding the theoretical benefits of beta-blockade in sepsis (i.e. decreased mortality/morbidity 2/2 decreased sympathetic innervation, inflammation, myocardial demand etc.) have been varied. However, esmolol has been demonstrated multiple times to be effective at reducing heart rate without significant adverse outcomes (i.e. no sig diff in mortality, refractory shock, or time on vasopressors).

Caveats/pitfalls

-most of the studies discuss “adequate resuscitation” prior to initiation of esmolol

-not studied in patients that also had significant cardiac dysfunction

-be aware that esmolol gtts can be a lot of volume and pts can become volume overloaded if boarding in the ED for an extended period of time

Cocchi MN, Dargin J, Chase M, et al. Esmolol to treat the hemodynamic effects of septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Shock. 2022;57(4):508-517.

Morelli A, Ertmer C, Westphal M, et al. Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1683.

Rehberg S, Joannidis M, Whitehouse T, Morelli A. Landiolol for managing atrial fibrillation in intensive care. European Heart Journal Supplements. 2018;20(suppl_A):A15-A18.

Zhang J, Chen C, Liu Y, Yang Y, Yang X, Yang J. Benefits of esmolol in adults with sepsis and septic shock: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2022;101(27):e29820.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Insulin infusion, diabetes mellitus, diabetic ketoacidosis, DKA, subcutaneous, long-acting (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/29/2022 by Kami Windsor, MD

(Updated: 9/21/2022)

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

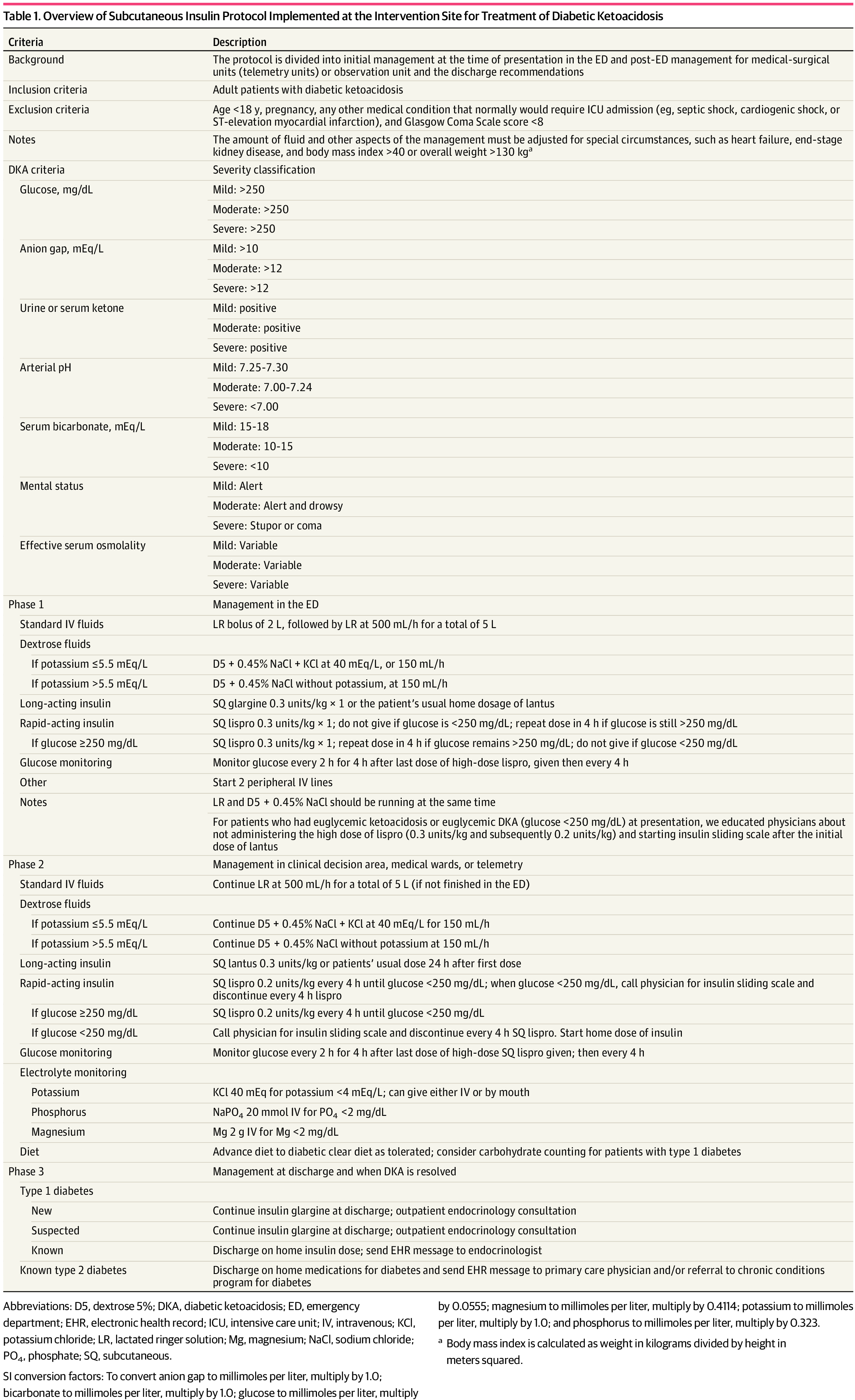

Background: It is classically taught that the tenets of DKA management are IV fluids, electrolyte repletion, and an insulin infusion that is titrated until approximately 2 hours after anion gap closure, when long-acting subcutaneous insulin is administered if the patient is tolerating oral intake. It has been previously found that earlier administration of subcutaneous long-acting insulin can shorten the time to anion gap closure, while other small studies have noted similar efficacy in subcutaneous insulin compared to IV in mild/moderate DKA.

A recent JAMA article presents a retrospective evaluation of a prospectively-implemented DKA protocol (see "Full In-Depth" section) utilizing weight-based subcutaneous glargine and lispro, rather than IV regular insulin, as part of initial and ongoing floor-level inpatient treatment.

When compared to the period before the DKA protocol:

The only exclusion criteria were age <18 years, pregnancy, and presence of other condition that required ICU admission.

Bottom Line: Not all DKA requires IV insulin infusion.

At the very least, we should probably be utilizing early appropriate-dose subcutaneous long-acting insulin. With ongoing ICU bed shortages and the importance of decreasing unnecessary resource use and hospital costs, perhaps we should also be incorporating subcutaneous insulin protocols in our hospitals as well.

As a part of the DKA protocol, patients:

Elevated BMI was not included in exclusion criteria, however the authors note that their DKA protocol has been amended to exclude patients >166kg due to concerns regarding insulin absorption.

Rao P, Jiang S, Kipnis P, et al. Evaluation of Outcomes Following Hospital-Wide Implementation of a Subcutaneous Insulin Protocol for Diabetic Ketoacidosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e226417. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.6417

Houshyar J, Bahrami A, Aliasgarzadeh A. Effectiveness of Insulin Glargine on Recovery of Patients with Diabetic Ketoacidosis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 May;9(5):OC01-5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12005.5883.

Mohamed A, Ploetz J, Hamarshi MS. Evaluation of Early Administration of Insulin Glargine in the Acute Management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2021;17(8):e030221191986. doi: 10.2174/1573399817666210303095633.

Karoli R, Fatima J, Salman T, Sandhu S, Shankar R. Managing diabetic ketoacidosis in non-intensive care unit setting: Role of insulin analogs. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011 Jul;43(4):398-401. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.83109.

Ersöz HO, Ukinc K, Köse M, Erem C, Gunduz A, Hacihasanoglu AB, Karti SS. Subcutaneous lispro and intravenous regular insulin treatments are equally effective and safe for the treatment of mild and moderate diabetic ketoacidosis in adult patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2006 Apr;60(4):429-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00786.x.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Vasopressors, Hypotension, Shock, Sepsis (PubMed Search)

Posted: 6/21/2022 by Mark Sutherland, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

Although it is well-documented that there is no true "maximum" dose of vasopressor medications, further blood pressure support as doses escalate to very high levels tends to be limited. As such, debate has raged in Critical Care as to when is the "right" time to start a second vasoactive medication. The VASST trial (Russell et al, NEJM, 2008) is considered to be the landmark trial in this area, and found a trend towards improvement with early addition of vasopressin to norepinephrine, but no statistically significant difference, and may have been underpowered.

Partly as a result of VASST, the pendulum has tended to swing towards maximizing a single vasoactive before adding a second over the past decade. The relatively high cost of vasopressin in the US has also driven this for many institutions. However, more recently a "multi-modal" approach, emphasizing an earlier move to second, or even third, vasoactive medication, is increasingly popular. Although cost is often prohibitive for angiotensin-2 given controversial benefits, many now advocate for targeting adrenergic receptors (e.g. with norepinephrine or epinephrine), vasopressin receptors (e.g. with vasopressin or terlipressin) and the RAAS system (e.g. with angiotensin 2) simultaneously in patients with refractory shock. A recent review by Wieruszewski and Khanna in Critical Care (see references) outlines this approach well.

Bottom Line: When to add a second vasoactive medication (e.g. vasopressin) for patients with refractory shock after a first vasoactive is controversial and not known. Current practice is trending towards earlier addition of a second (or third) agent, especially if targeting different receptors, but there is limited high-quality evidence to support this approach. Many practicioners (including this author) still follow VASST and consider vasopressin once doses of around 5-15 micrograms/min (non-weight based) of norepinephrine are reached.

Wieruszewski PM, Khanna AK. Vasopressor Choice and Timing in Vasodilatory Shock. Crit Care. 2022 Mar 22;26(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03911-7. PMID: 35337346; PMCID: PMC8957156.

Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, Gordon AC, Hébert PC, Cooper DJ, Holmes CL, Mehta S, Granton JT, Storms MM, Cook DJ, Presneill JJ, Ayers D; VASST Investigators. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 28;358(9):877-87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067373. PMID: 18305265.

Early addition of Terlipressin: Article Title (ijccm.org)

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 6/14/2022 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Vasopressor Tips in the Critically Ill

Legrand M, et al. Ten tips to optimize vasopressor use in the critically ill patient. Intensive Care Med. 2022; online ahead of print.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: low tidal volume, Emergency Department (PubMed Search)

Posted: 5/31/2022 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

Background:

Lung-protective ventilation with low-tidal volume improves outcome among patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. The use of low tidal volume ventilation in the Emergency Departments has been shown to provide early benefits for critically ill patients.

Methodology:

A systemic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing outcomes of patients receiving low tidal volume ventilation vs. those who did not receive low tidal volume ventilation.

The authors identified 11 studies with approximately 11000 patients. The studies were mostly observational studies and there was no randomized trials.

The authors included 10 studies in the analysis, after excluding a single study that suggested Non-low tidal volume ventilation was associated with higher mortality than low tidal volume ventilation (1).

Results:

Comparing to those with NON-Low tidal volume ventilation in ED, patients with Low-Tidal volume ventilation in ED were associated with:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

Although there was low quality of evidence for low tidal volume ventilation in the ED, Emergency clinicians should continue to consider this strategy.

1. Prekker ME, Donelan C, Ambur S, Driver BE, O'Brien-Lambert A, Hottinger DG, Adams AB. Adoption of low tidal volume ventilation in the emergency department: A quality improvement intervention. Am J Emerg Med. 2020 Apr;38(4):763-767. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.026. Epub 2019 Jun 15. PMID: 31235218.

2. De Monnin K, Terian E, Yaegar LH, Pappal RD, Mohr NM, Roberts BW, Kollef MH, Palmer CM, Ablordeppey E, Fuller BM. Low Tidal Volume Ventilation for Emergency Department Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Practice Patterns and Clinical Impact. Crit Care Med. 2022 Jun 1;50(6):986-998. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005459. Epub 2022 Feb 7. PMID: 35120042.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 5/24/2022 by Caleb Chan, MD

Click here to contact Caleb Chan, MD

-If the patient is able to maintain mentation/airway/SpO2/hemodynamics and cough up blood, intubation is not immediately necessary

-If you do intubate, intubate with the largest ETT possibly to faciliate bronchoscopic interventions and clearance of blood

-The CT scan that typically needs to be ordered is a CTA (not CTPA) with IV con

-See if you can find prior/recent imaging in the immediate setting (e.g. pre-existing mass/cavitation on R/L/upper/lower lobes)

-Get these meds ready before the bronchoscopist gets to the bedside to expedite care:

-If the pt's vent suddenly has new high peak pressures or decreased volumes after placement of endobronchial blocker, be concerned that the blocker has migrated

Charya AV, Holden VK, Pickering EM. Management of life-threatening hemoptysis in the ICU. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(8):5139-5158.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 5/23/2022 by William Teeter, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

Encountered a situation in CCRU where we needed to prepare for a patient exsanguinating from gastric varices, and found a great summary of the different types of gastroesophageal balloons from EMRAP.

Summary: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yv4muh0hX7Y

More in depth video on the Minnesota tube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4FHIiA_doWU

Nice review article: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0736467921009136

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: in-hospital cardiac arrest, IHCA, resuscitation, code, epinephrine, vasopressin, methylprednisolone (PubMed Search)

Posted: 5/2/2022 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Based on prior studies1 indicating possibly improved outcomes with vasopressin and steroids in IHCA (Vasopressin, Steroids, and Epi, Oh my! A new cocktail for cardiac arrest?), the VAM-IHCA trial2 compared the addition of both methylprednisolone and vasopressin to normal saline placebo, given with standard epinephrine resuscitation during in hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA).

The use of methylprednisolone plus vasopressin was associated with increased likelihood of ROSC: 42% intervention vs. 33% placebo, RR 1.3 (95% CI 1.03-1.63), risk difference 9.6% (95% CI 1.1-18.0%); p=0.03.

BUT there was no increased likelihood of favorable neurologic outcome (7.6% in both groups).

Recent publication on evaluation of long-term outcomes of the VAM-ICHA trial3 showed that, at 6-month and 1-year follow-up, there was no difference between groups in:

Bottom Line: Existing evidence does not currently support the use of methylprednisolone and vasopressin as routine code drugs for IHCA resuscitation.

Basic study characteristics:

Some of the limitations:

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 4/19/2022 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

ED Low-Tidal Volume Ventilation

Monnin KE, et al. Low tidal volume ventilation for emergency department patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis on practice patterns and clinical impact. Crit Care Med. 2022; published online Feb 7, 2022.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: APRV, low tidal volume, COVID-19 (PubMed Search)

Posted: 4/5/2022 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

During the height of the pandemic, a large proportion of patients who were referred to our center for VV-ECMO evaluation were on Airway Pressure Release Ventilation (APRV). Does this ventilation mode offer any advantage? This new randomized control trial attempted to offer an answer.

---------------

1.Settings: RCT, single center

2. Patients: 90 adults patients with respiratory failure due to COVID-19

3. Intervention: APRV with maximum allowed high pressure of 30 cm H20, at time of 4 seconds. Low pressure was always 0 cm H20, and expiratory time (T-low) at 0.4-0.6 seconds. This T-low time can be adjusted upon analysis of flow-time curve at expiration.

4. Comparison: Low tidal volume (LTV) strategy according to ARDSNet protocol.

5. Outcome: Primary outcome was Ventilator Free Days at 28 days.

6.Study Results:

7.Discussion:

8.Conclusion:

APRV was not associated with more ventilator free days or other outcomes among patients with COVID-19, when compared to Low Tidal Volume strategies in this small RCT.

Ibarra-Estrada MÁ, García-Salas Y, Mireles-Cabodevila E, López-Pulgarín JA, Chávez-Peña Q, García-Salcido R, Mijangos-Méndez JC, Aguirre-Avalos G. Use of Airway Pressure Release Ventilation in Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure Due to COVID-19: Results of a Single-Center Randomized Controlled Trial. Crit Care Med. 2022 Apr 1;50(4):586-594. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005312. PMID: 34593706; PMCID: PMC8923279.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: OHCA, shock, epinephine, norepinephrine, cardiac arrest (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/23/2022 by William Teeter, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

The use of catecholamines following OHCA has been a mainstay option for management for decades. Epinephrine is the most commonly used drug for cardiovascular support, but norepinephrine and dobutamine are also used. There is relatively poor data in their use in the out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). This observational multicenter trial in France enrolled 766 patients with persistent requirement for catecholamine infusion post ROSC for 6 hours despite adequate fluid resuscitation. 285 (37%) received epinephrine and 481 (63%) norepinephrine.

Findings

Limitations:

Summary:

Norepinephrine may be a better choice for persistent post-arrest shock. However, this study is not designed to sufficiently address confounders to recommend abandoning epinephrine altogether, but it does give one pause.

Epinephrine versus norepinephrine in cardiac arrest patients with post-resuscitation shock. Intensive Care Med. 2022 Mar;48(3):300-310. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06608-7.

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 3/15/2022 by Duyen Tran, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Duyen Tran, MD

Acute liver failure is defined as new and rapidly evolving hepatic dysfunction associated with neurologic dysfunction and coagulopathy (INR >1.5). Most common cause of death in these patients are multiorgan failure and sepsis. Drug-induced liver injuy most common cause in US, with viral hepatitis most common cause worldwide.

Management of complications associated with acute liver failure

Montrief T, Koyfman A, Long B. Acute liver failure: A review for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2019 Feb;37(2):329-337. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.032. Epub 2018 Oct 22. PMID: 30414744.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Mechanical Ventilation, PEEP (PubMed Search)

Posted: 3/2/2022 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

How to set the correct PEEP remains one of the most controversial topics in critical care. In fact, just on UMEM Pearls there are 55 hits when one searches for PEEP, including this relatively recent pearl on PEEP Titration.

A recent Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis looked at existing trials on this issue. They found that:

1) Higher PEEP strategies were associated with a mortality benefit compared to lower PEEP strategies

2) Lung Recruitment Maneuvers were associated with worse mortality in a dose (length of time of the maneuver) dependent fashion.

This fits with recent literature and trends in critical care and bolsters the feeling many intensivists are increasingly having that we may be under-utilizing PEEP in the average patient.

Bottom Line: As an extremely broad generalization, we would probably benefit the average patient by favoring higher PEEP strategies, and avoiding lung recruitment maneuvers. Do keep in mind that it is probably best to continue lower PEEP strategies in patient populations at high risk of negative effects of PEEP (e.g. COPD/asthma, right heart failure, volume depleted with hemodynamic instability, bronchopleural fistula) until these groups are specifically studied.

Dianti J, Tisminetzky M, Ferreyro BL, Englesakis M, Del Sorbo L, Sud S, Talmor D, Ball L, Meade M, Hodgson C, Beitler JR, Sahetya S, Nichol A, Fan E, Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Slutsky AS, Ferguson ND, Serpa Neto A, Adhikari NK, Angriman F, Goligher EC. Association of PEEP and Lung Recruitment Selection Strategies with Mortality in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Feb 18. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1972OC. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35180042. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35180042/

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 2/22/2022 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State (HHS)

Long B, Willis GC, Lentz S, et al. Diangosis and management of the critically ill adult patient with hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. J Emerg Med. 2021;61:365-75.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Saline, balanced fluid, critically ill, mortality (PubMed Search)

Posted: 2/8/2022 by Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

(Updated: 2/8/2026)

Click here to contact Quincy Tran, MD, PhD

The debate is still going on: Whether we should give balanced fluids or normal saline.

Settings: PLUS study involving 53 ICUs in Australia and New Zealand. This was a double-blinded Randomized Control trial.

Study Results:

Discussion:

Conclusion:

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 1/27/2022 by William Teeter, MD

Click here to contact William Teeter, MD

A prospective, randomized, open-label, parallel assignment, single-center clinical trial performed by an anesthesiology-based Airway Team under emergent circumstances at UT Southwestern.

801 critically ill patients requiring emergency intubation were randomly assigned 1:1 at the time of intubation using standard RSI doses of etomidate and ketamine.

Primary endpoint: 7-day survival, was statistically and clinically significantly lower in the etomidate group compared with ketamine 77.3% (90/396) vs 85.1% (59/395); NNH = 13.

Secondary endpoints: 28-day survival rate was not statistically or clinically different for etomidate vs ketamine groups was no longer statistically different: 64.1% (142/396) vs 66.8% (131/395). Duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU LOS, use and duration of vasopressor, daily SOFA for 96 hours, adrenal insufficiency not significant.

Other considerations:

1. Similar to a 2009 study, ketamine group had lower blood pressure after RSI, but was not statistically significant. 2

2. Etomidate inhibits 11-beta hydroxylase in the adrenals. Associated with positive ACTH test and high SOFA scores, but not increased mortality.2

3. Ketamine raises ICP… just kidding.

Etomidate versus ketamine for emergency endotracheal intubation: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021 Dec 14. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06577-x. Online ahead of print.

Jabre P, Combes X, Lapostolle F, et al.; KETASED Collaborative Study Group. Etomidate versus ketamine for rapid sequence intubation in acutely ill patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009 Jul 25;374(9686):293-300. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60949-1. Epub 2009 Jul 1. PMID: 19573904.

Bruder EA, Ball IM, Ridi S, Pickett W, Hohl C (2015) Single induction dose of etomidate versus other induction agents for endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(1):CD010225. https://doi.org/10.1002/1ecweccccccccccc4651858.CD010225.pub2

Wang, X., Ding, X., Tong, Y. et al. Ketamine does not increase intracranial pressure compared with opioids: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Anesth 28, 821–827 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-014-1845-3

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 1/18/2022 by Duyen Tran, MD

Click here to contact Duyen Tran, MD

Clinical pearls for hypothermic cardiac arrest

Paal P, Gordon L, Strapazzon G et al. Accidental hypothermia–an update. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24(1). doi:10.1186/s13049-016-0303-7

Pasquier M, Rousson V, Darocha T et al. Hypothermia outcome prediction after extracorporeal life support for hypothermic cardiac arrest patients: An external validation of the HOPE score. Resuscitation. 2019;139:321-328. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.03.017

Misch M, Helman A. Accidental Hypothermia and Cardiac Arrest | CritCases | EM Cases. Emergency Medicine Cases. http://emergencymedicinecases.com/accidental-hypothermia-cardiac-arrest. Published 2019. Accessed January 18, 2022.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: trauma, pneumothorax, positive pressure ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, tension pneumothorax (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/14/2022 by Kami Windsor, MD

Click here to contact Kami Windsor, MD

Background: Conventional medical wisdom long held that patients with pneumothorax (PTX) who require positive pressure ventilation (PPV) should undergo tube thoracostomy to prevent enlarging or tension pneumothorax, even if otherwise they would be managed expectantly.1

Bottom Line: The cardiopulmonar-ily stable patient with small PTX doesn’t need empiric tube thoracostomy simply because they’re receiving positive pressure ventilation. If you are unlucky enough to still have them in your ED at day 5 in these COVID times, provide closer monitoring as the observation failure rate may increase dramatically around this time.

Category: Critical Care

Keywords: Calcium, Cardiac Arrest, ACLS, Code Blue (PubMed Search)

Posted: 1/5/2022 by Mark Sutherland, MD

Click here to contact Mark Sutherland, MD

There are several well known medications that we tend to give by default during cardiac arrests. It seems like for each of them, every few years someone does an RCT to see if they really help anybody, and we're all disappointed by what they find. Well... prepare to be disappointed again, I'm afraid.

These Danish authors randomized 391 patients in cardiac arrest to either calcium or saline (given IV or IO). They gave 2 doses of either calcium chloride or saline, with the first dose being along with the first epi dose. Primary outcome was ROSC. They also looked at modified Rankin at 30 and 90 days.

The trial was stopped early for harm. Now, we all know the dangers of interpreting studies that were stopped early, but this doesn't look great for calcium. 19% of the calcium group had ROSC compared to 27% of the saline group (p = 0.09). Percentage of patients alive, and with favorable mRS at 30 days also both favored the saline group (although also not statistically significantly). By the way, of the patients who had calcium levels sent, 74% in the calcium group, vs 2% in the saline group, were hypercalcemic. Whether that had anything to do with the outcome, we may never know.

Bottom Line: Is this saying that calcium hurts patients in cardiac arrest? Maybe... but I don't think this is high quality enough data to draw that conclusion. At the very least, however, just giving everyone in arrest calcium is probably not terribly helpful. If you have a reason to give it (known severe hypocalcemia, recent parathyroid surgery, suspected hyperkalemia, etc) then go for it, otherwise you can probably focus your resus on more important things.

Vallentin MF, Granfeldt A, Meilandt C, et al. Effect of Intravenous or Intraosseous Calcium vs Saline on Return of Spontaneous Circulation in Adults With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326(22):2268–2276. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.20929

Category: Critical Care

Posted: 12/28/2021 by Mike Winters, MBA, MD

Click here to contact Mike Winters, MBA, MD

The BOUGIE Trial

Driver BE, et al. Effect of use of a bougie vs endotracheal tube with stylet on successful intubation on the first attempt among critically ill patients undergoing tracheal intubation. JAMA. 2021. Published online December 8, 2021